Sunday, May 12, 2002

By Tenzin Bhagen

The Grand Rapids Press

When I was little, my mother would look at my feet, and, reciting a Tibetan saying, tell me she could see a sign that I would be going far away. I always liked it when she said that. I don't know why. It was kind of a painful memory after I was gone from Tibet. Whenever I wished I could see my mother, I remembered those words. It had been 15 years since I had seen her.

My mother has been a great influence in my life, especially my Tibetan way of life. She taught me religious beliefs and told me hundreds of Tibetan folk tales, all of which shaped my beliefs. More than that, her love and compassion toward me made me a different person than I otherwise might have been as I grew up under heavy communist propaganda.

For Tibetans, mothers are the kindest peoplein the world. This concept also serves religious purposes. As part of developing love and compassion for all sentient beings, they say everyone is one's mother at some point in one's previous lives, and, therefore, one must pay their kindness back. To me, it was hard to think how to pay back this woman's kindness.

I escaped from Tibet in 1986 in pursuit of an education. I walked across the Himalayas and went to India, via Nepal. I had no passport or ID, nothing that identified who I was. Until January 2001, when I became an American citizen, I had no passport. As soon as my spring semester at Grand Valley State University ended, I rushed to the Chinese consulate in San Francisco to get the visa to travel to Tibet. I felt very unfortunate that I had to go to the Chinese government office to get a visa to visit my own country, but that was the only way I could visit my family. The Chinese government wants to believe Tibet is in China. It would be an insult for a Chinese governmental official if I told him I wanted to get a visa to "Tibet."

With the help of a couple from Grand Rapids and other friends --, and, of course, my magic plastic cards -- I got enough money to travel and buy a ticket. In June, I flew from San Francisco International Airport to Beijing. It was an 11-hour nonstop flight. I couldn't believe what it was like to be a citizen of an independent nation. Just because I had a passport, I could move from one side of the earth to the other in a short time.

That night in my hotel was the longest I ever had. I was awake the whole night. All the TV channels were in Chinese. I watched a movie about how the Communists took over China. The following day, I flew to Chengdu, where tourists who want to go to Tibet must get a permit. I was registering at the front desk of the hotel when someone greeted me in Tibetan. A mischievous looking man sitting on a couch near the front desk said, "Jo la, ganei peb pai," (Brother, where have you come from?). He was a Tibetan who recognized I was, too.

"Oh, are you a Tibetan?" I asked in Tibetan, pretending I was happy to see him. I should have been happy to see a fellow Tibetan in a Chinese city where I never had been before. Unfortunately, in that part of the world, one cannot trust strangers. He asked me if I was going to Tibet. I said I was not sure, but I could see from his face he knew I was. He said he knew of no Tibetans from abroad who had been given a permit recently. I could not imagine returning to the United States without seeing my family.

That night, I called my friends in Tibet and asked them to find a way to get the permit for me before I tried myself in Chengdu. They tried to get it through connections. Being under Chinese control for about half a century, Tibetans learned to do anything, one must know how to "break the ribs" of authorities (a Tibetan expression to bribe). Some of my businessmen friends are quite handy in doing so. However, this time, they came to their wits' end.

The hallways of Chengdu airport were full of people rushing to their destinations. Pushing other people seemed to be everyone's cultural right. The slow moving line and my heavy bags made me sweat, but I would not take off my coat until I was in my seat in the airplane. Whether I would make it to the airplane or not was another story.

I walked to the security check-in counter. I chose the noon flight, because it was peak time. A woman and a man in blue uniforms looked at my ID. I knew this moment would determine the two fates lying in front of me: Tibet or jail. They looked at my face a couple of times. Then they returned the ID and ticket. Relief.

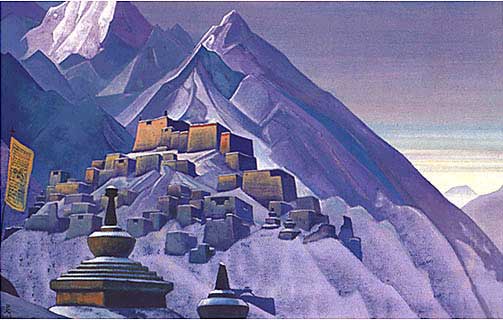

Not many minutes after taking off from Chengdu, I saw the majestic snow-capped mountains rising like white curtains that divided Tibet from China. I felt these mountains always have kept the legacy of the ancient great kings of Tibet alive. No matter what communist China has done to Tibetans or said about Tibet, these mountains know the truth. For a moment, I blamed them for not speaking out. But then I realized they do speak in their own way. When the satellite takes pictures, these mountains make a geographical gesture that says this is Tibet.

When the first ranges of the mountains were right under my eyes, I remembered the testimonies of Old Khampas. The Old Khampas, some time supported by a handful of Tibetan soldiers, defended Tibet from Chinese troops for generations, even after the Tibetan kings long had gone and the government in the central Tibet was weak. I knew these mountains were not as white as they appeared to be. They were stained with the blood of Tibetan defenders and Chinese invaders. They carry the footprints of the ancient warriors of Tibetan kings, who once passed these mountains and overthrew a Chinese empire by their force. I felt I was seeing some thousands-year-old warriors who now wait for a justice from the nonviolence and compassionate struggle of Tibet.

When the plane landed at Lhasa Airport, I looked out the window and saw about a dozen policemen lined up at the airport ground. It was obvious they were waiting for someone from my plane. I stayed in my seat until most of the people left. The police didn't leave. I got out of the plane and inhaled the fresh air of Tibet I had not breathed for 15 years.

I felt a joyful sense from deep inside as I put my foot on Tibetan land. For a moment, I felt as if I were the only person on that flat ground. I walked cautiously over to the gate. Later I learned there was a chief police officer from one of China's provinces in my plane, and the policemen at the airport were there to welcome him.

In the early morning, I went to Tsuglag Khang temple to see Jowo Shakya Muni, a statue of Buddha every Tibetan must see in his or her lifetime. Inside the temple, cameras were watching from every corner. However, they didn't stop the Tibetans' brave praying. A middle-age woman next to me drew my attention. She was praying very loudly, saying "Yezhi Norbu kutse tenpar shog" (may the Dalai Lama live long), and "Dekyi nyima nyurdu sharbar shog, (may the sun of happiness rise soon). I was amazed. She kept praying again and again all the way. She was not the only one praying, but most of the people were praying softly.

The Chinese must think the people inside the temple were just praying regular mantras because I know if someone said "long live Dalai Lama" outside that temple, they immediately would be arrested.

In Lhasa, the only place I felt the spirit of the Tibet was inside the Tsuglag Khang Temple. Even the Potala, the Dalai Lama's palace, is different from how it used to look. The town of Shul, which was at the foot of the palace, has been demolished. In front of the palace, a Tiananmen-like square building was built. A huge stage in front of it features a red banner stretched horizontally: "Celebrate the 50th anniversary of peaceful liberation of Tibet -- 1951-2001." Nothing could be more ironic than this. About four blocks away at Norbu Linka was where the massacre of about 10,000 Tibetans occurred during three days in March 1959, when the People's Liberation Army of China gunned down the Tibetan freedom fighters.

After staying one night in Lhasa, where I met with friends, I left for my hometown. My friends' car had no license plate, but neither do most of the foreign cars in Tibet. The car-dealers smuggle them into Tibet from China. Once the cars arrive in Tibet, they mostly are bought by the authorities.

When we were passing the city limit, the police stopped us. A young Chinese woman in a police uniform looked inside our car and asked where the license plate was. My friend driving the car, a big man in a suit with an authoritative voice, said in Chinese, "Of course, it is in my department."

"What department are you from?" she asked. At that moment, a man in uniform interrupted her and told us, "Go, go." It wasn't the only time we were stopped on the road, but my friends managed to go without trouble. One time they gave a couple of dozen cigarettes to a group of young officers.

The mountains became bigger and greener as we drove east. We met a few Tibetans going to Lhasa by prostrating on the road. This is a traditional religious practice only a few people do. These people move only by the length of their bodies after each prostration -- measuring the entire road by the length of one's own body. It takes many months before they arrive at Lhasa.

When I saw the mountain tops of my area, I could not be happier. A couple of vultures flew over us. "These vultures might be the mountain gods who are here to welcome you," my friends said to me. After four days driving from Lhasa, we arrived in my area. At the first village, we stopped our car, and some people brought us tea. They told me my mother had moved up in the mountains to visit one of my sisters.

My friends thought we could drive up the mountain to see my mother. We got stuck in a river, near a village. A Tibetan man with a truck came to help us. On his way, his truck got stuck in the mud. Two old men and many children from the village came to help us. The children were about 4 to 7 years old. They moved small rocks to put under the truck. I felt sad to see there were no schools for these children. It reminded me of my childhood -- playing and running around, no hope for future. The truck finally got out of the mud and was able to pull our car out of the river.

My mother did not know that I was coming. She was told I was planning to come this year, but she was not sure if it was true, since every few years I had been sending her messages saying I would be coming "next year." As we stopped our car above my sister's summer house, a man who had come with us from the village ran down to tell the news about my arrival. I had received a picture of my mother a couple of months before leaving the United States, so I knew how my mother looked. When I saw the picture in San Francisco, I wept. I felt a great regret of leaving her. For a moment, I wished I had stayed in Tibet to serve my mother. I felt very selfish. Now I was about to see her in real life.

It was a very powerful experience. It was beyond a normal sense of joy or fear. Every second was longer than before, and every step had a value -- I was walking toward my mother. My mother was running up the hill. "My son! Is it really you?" My sister followed her. Both were crying.

I, too, cried and hugged them and touched my forehead to theirs, a Tibetan nomadic tradition. My sister now looked as old as my mother when I left Tibet. My mother, on the other hand, looked stronger than I expected. She had become a nun. Her hair was shaved.

I wished I could bring her to America, but I realized it would be too hard to do so. She wouldn't be happy, as I would not be able to be with her all the time, and she wouldn't be able to communicate with anyone else.

"It must be the Three Jewels (Buddha, Dharma and Sanga) that gave us the chance to reunite," my mother said, still crying. "No human being could be happier than me today!"

*******************************************************

When will Tibet be free? was constant question When I visited my sister (in Tibet), she was sick and in bed. I gave her some blessings. That's all I could do. There was no doctor to call, no hospitals to take her to that were close. The nonexistent health-care system and lack of schools for children are what I see as the most critical situation for the survival of Tibet and Tibetans. Politically, this undermines the strength of Tibetan people's struggle of freedom and cultural preservation.

Many of the people I saw asked me when Tibet would be free. The desperation was in their souls. "My father had waited for so many years to see it (Tibetan independence) happen," a friend who worked for the Chinese government said. "It didn't happen in his life time (his father passed away couple years ago). Now I don't know if it will happen in my life time either."

One elderly man, who is in his 60s and had been in prison for many years for being a freedom fighter, didn't show much frustration. He is the only survivor of his five brothers, all of whom went to prison and died. He now tries to protect a small forest. The ancient forest had been clearcut by a Chinese lumber team. He told me he has started to protect it since the Dalai Lama's 60th birthday. He held my hands very tightly all the time when he asked me about Tibetan movement outside. I could see he expected me to tell him more than I had to share.

I know these very people won't tell what they told me to any other people from outside, even if foreign journalists would have interviewed them. These people have suffered so much for words they've said and actions they've taken. I sometimes see articles written foreigners who visit Tibet. These journalists treat the words heard from Tibetans the same way they would treat the words of people in the free world. I am not trying to say what Tibetans inside Tibet say is not legitimate. But through my experience of being a Tibetan and growing up in Tibet, I know that the majority of Tibetans in Tibet cannot utter what is deep insIde of their heart to any channel which the Chinese government can monitor.

I wasn't sure if I was going to write this story. However, after coming back to U.S., I feel that I have the moral responsibility to tell what I have seen and learned while traveling in Tibet to the world as the Tibetans want the world to know what is going on there. Although I lack courage to write because my English is a second language, I feel I am one of the people who have the closest access to know the truth about Tibetan people's lives and their wish.

Editor's note: Tenzin spent about a month in Tibet before returning to the United States. He'll spend this summer in Taiwan studying Chinese before going to England for a year to study, then return to Grand Valley State University in 2003.